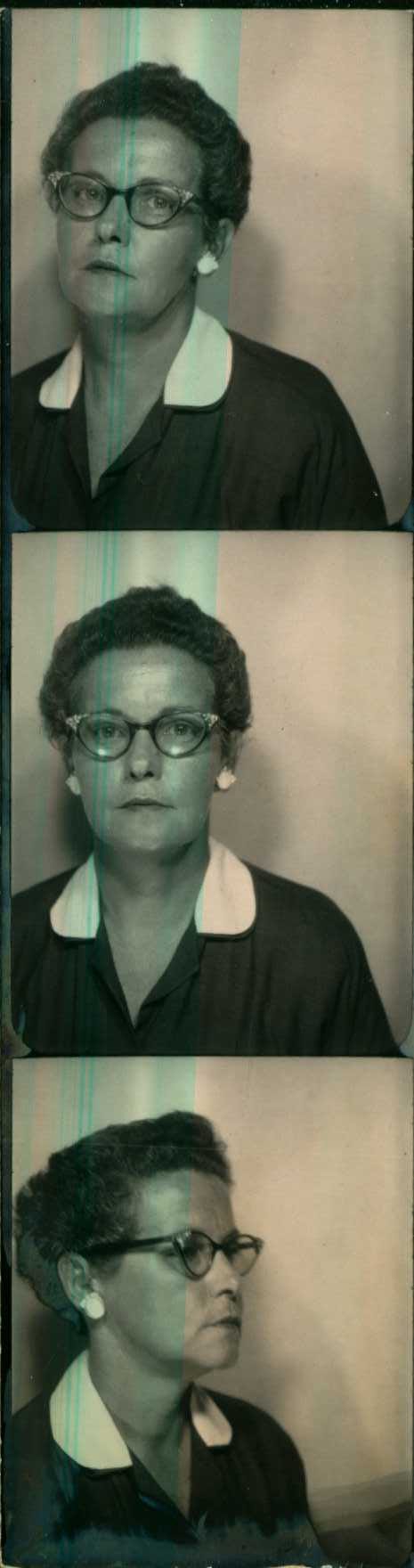

I have never understood mean people. My Big Granny was mean. My mother’s mother grew up on a farm outside of Taylor, Texas and she took a particular glee in telling stories of wringing the necks of chickens and skinning hogs. Her mean streak extended to her three children, especially my mother the middle child, but I could never understand where it came from. The only explanation I ever heard from my family about her tendency toward cruelty was that she’d always wanted “a big house on a hill” and since she never got that, so she died as she lived: embittered.

There is something in the set of Marjorie Taylor Greene’s jaw that follows the same contours of meanness that my Big Granny’s expression had. The Republican representative in Congress from Georgia has been making a name for herself in recent weeks by shouting “liar” at President Biden during the State of the Union address and, more recently, by declaring that we need a “national divorce.” Jamelle Bouie does a great job pointing out the ridiculous folly of trying to separate people into “red” and “blue” states, writing at the NYTimes, he writes, “No matter how small you go… you run into the simple fact that there’s no such thing as a truly homogeneous political community.” Aside from the practical impossibility of her facile dream of red-blue binaries, Greene’s brand seems animated by a performative ferocity that is part cross-fit-warrior and part mean-girl.

I missed the whole mean-girl-feminism thing when I was writing my book on white lady shenanigans but fortunately there is a new book coming that takes this up: Mean Girl Feminism: How White Feminists Gaslight, Gatekeep, and Girlboss by Kim Hong Nguyen (due out in early 2024). I was lucky enough to read an early draft of this book and it’s excellent. Nguyen’s book taught me a lot about this side of what we do as white women when we adopt this mean-girl approach at the same time we embrace feminism.

I think it’s this last bit that tripped me up. Until now, I haven’t been able to understand “mean girl” as a modifier of “feminism.” My Big Granny was certainly no feminist, just mean. That “house on a hill” she wanted so desperately was a house she wanted some man to buy her and was pissed off most of her life because she didn’t get that. Marjorie Taylor Greene is definitely a mean girl, and is doing things like getting elected to Congress that I was always taught would make things better for all women, and yet, she is decidedly not a feminist. Nguyen’s book and a conversation I had with Brittney Cooper helped me understand the mean-girl dynamic.

At a dinner party some months ago I got invited to by my friend Shawnda Chapman (thanks, Shawnda!), I ended up seated across from Brittney Cooper, author of Eloquent Rage: A Black Woman Discovers Her Superpower. As we got to chatting about a wide range of things, Cooper mentioned that she’d heard of my book and asked, “How’s the reception been?” I replied that it had been “chilly.” Then, I recounted a story about a speaking invitation I’d gotten to a small, liberal arts college in the area in which almost no one had showed up to a series of planned talks by me about the book, and I suggested it said more about the people who didn’t show than it did about the book. Then, Cooper said this: “Yeah, you white women do that mean girl shit to each other.” That was when the penny dropped for me. I’ve seen this play out among white women in the reception to my book in any number of ways.

The dilemma for me, and I think in a way all of us who want a better world, is what do we do about the mean girls, feminist or not? My attempt was to write a book, Nice White Ladies, which I saw as an act of “calling in” my fellow white women. Even though there’s no chapter in that book on mean girls, I thought there would be something useful in telling stories from my own life, about my mother, my mean Big Granny, and the rest of my family, that might help the people reading the book calm down long enough to examine their own lives. Part of my effort in that book, too, was to not do the easy (and mean) trick of just pointing to white women like Marjorie Taylor Greene and dunking on them for all the harm they cause (why write a whole book just to be mean?). But, MTG and women like my Big Granny, are unlikely to pick up my book unless it’s to ban it.

With much respect to Loretta Ross and the SURJ team’s calling in team (where I’ve been practicing this skill), I’ve come to see there are limits to calling in. There are some white women who not only don’t want to be called in, they don’t think they need it and are ready to fight you (or, call their lawyers) for even mentioning their name in the context of causing harm. I’ve had this happen to me twice now in response to the book and, well, it’s easy to see the threat of a defamation lawsuit as just one more instance of mean girls in action, feminist or not.

The “nice” side of white feminism is one that is rooted in an investment in the idea of one’s own innocence when it comes to white supremacy. There are a whole range of defenses that we have built to reassure ourselves of this, structures really, that keep us ensconced in whiteness.

We, white women, are the majority of those who go to work in “helping” professions, like nursing, K-12 teaching, social work, and in international development. We, white women, have co-created what the writer Teju Cole has called the white-savior industrial complex. Cole, writing at The Atlantic (2012), points out: “A nobody from America or Europe can go to Africa and become a godlike savior or, at the very least, have his or her emotional needs satisfied.” This dynamic happens in a million different ways, including the save-the-animals campaigns and light-and-love wellness gambits.

We, white women, choose to live in all-or-mostly-white neighborhoods because we are concerned about safety, aesthetics, and so we don’t have to bother with any one different than ourselves. We, white women, send our kids to schools all-or-mostly-white schools because we just “want them to have the best.”

Sometimes people will ask me who I wrote the book for and the answer is that I wrote this for the rest of us: those of us who are brave enough to examine our own lives and are not so dead inside that the only way we can feel alright in our own skin is to be mean to someone else. I come back, again and again, to Nobel Laureate Toni Morrison, who (in 1993) asked us to contemplate who we are without whiteness:

If I take your race away, and there you are, all strung out. And all you got is your little self, and what is that? What are you without racism? Are you any good? Are you still strong? Are you still smart? Do you still like yourself? I mean, these are the questions. Part of it is, "yes, the victim. How terrible it's been for black people." I'm not a victim. I refuse to be one... if you can only be tall because somebody is on their knees, then you have a serious problem. And my feeling is that white people have a very, very serious problem and they should start thinking about what they can do about it. Take me out of it.

Ms. Morrison’s line, “if you can only be tall because somebody is on their knees, then you have a serious problem,” is really what I think is going on for people like my Big Granny and for Marjorie Taylor Greene. At a very deep level, they are afraid that they are nothing without being “better than” someone else. As for the nice white ladies in the helping professions, it’s her line about ‘How terrible it’s been for black people.’ We have to move beyond our fears and our misguided notion that race is only something for those we deem “Others.”

I know it wasn’t possible to call in my Big Granny, and I try to imagine a world in which Marjorie Taylor Greene could change her destructive ways, because I believe in the hope of transformation.

Until then, the rest of us will keep on doing the work.

I’ve been (given the adventures in consulting) running into this archetype everywhere and finding that person, the Nice White Lady Who Is Never To Be Told She’s Part of Any Problem, to be consistently the biggest challenge. And thinking a lot about why that is. Thanks for helping us all see clearly in this mess!

I truly love your writing and the way you can insert your experience and life into the current political and social landscapes. I’m curious: how has it shaped your identity? The fact that some white women reject what you write, how have you managed that?