Review: "SUFFS" Goes Full White Feminism

New musical attempts to reclaim suffrage movement and fails

A ho-hum score without a single transcendent, let alone hummable, tune. A set that is mostly wood-paneling. Dowdy period costumes. A plot that veers so far from historical accuracy in its embrace of a myopic version of feminism that it stretches the limits of credulity for anyone except those already invested in that view.

This is “SUFFS: The Musical,” which just opened at The Magic Box Theater this week. Although there are enthusiastic performances from the cast, the script is as wooden as the set. If one were to imagine a world in which the contributions of intersectional feminism never existed and in that world one were to create a musical that completely and fully centered white women’s experiences as The Universal Woman, then it would look very much like the ill-conceived and cringey “SUFFS.”

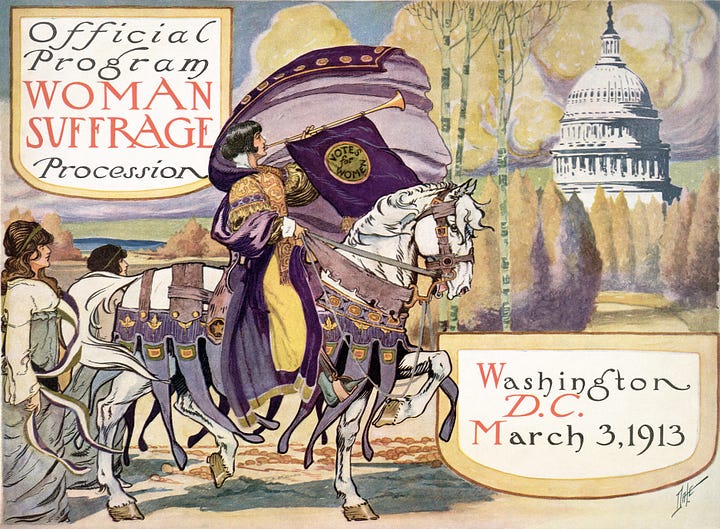

The musical begins in 1913 with Alice Paul (Shaina Taub, playwright and lead actor) organizing the Woman Suffrage Procession. As with any creative project, these are intentional choices that the play’s creators make to tell one particular story and exclude other stories.

All of the characters in the show are draw from the book, Jailed for Freedom, written by the suffragist Doris Stevens, also portrayed in the play. Her book documents the internecine conflicts between the National Woman’s Party (NWP), which fought for a national Equal Rights Amendment and the National American Woman’s Suffrage Party (NAWSA), which worked to get votes for women on a state-by-state basis. Both organizations were white, with the NWP appealing to a younger, more working-class constituency while the NAWSA appealed to older, mostly middle-class women. Black women (and other women of color) were excluded from these all-white organizations and started their own. The National Association of Colored Women (NACW), whose motto was “lifting as we climb,” included members such as Ida B. Wells-Barnett and Mary Church Terrell. The NACW was an early contender for my dissertation topic, so I’ve spent a little bit of time in the archives looking at the records of the organization and it is a rich history but that is almost entirely erased in “SUFFS.”

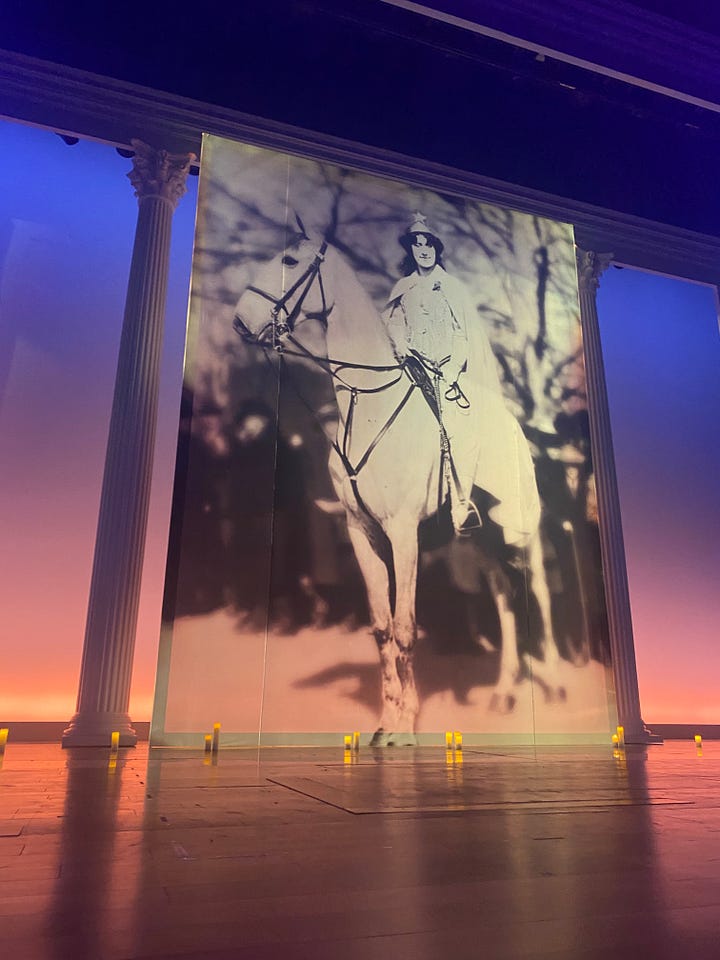

The opening sets up a conflict with the older activist Carrie Chapman Catt (Jenn Colella). The generational difference between these two white feminist activists is meant to serve as the central dramatic tension in the play but this feels forced. What it does more effectively is set up a series of age-related punchlines that landed well with the audience of mostly older, white women. In the play, it’s not clear what the stakes are in this conflict for either character except for the tactics they choose in their demands for the vote. Inez Milholland (Hannah Cruz), is another character based on an actual historical figure, appears as she did in the procession: atop a white horse.

After the procession, the play takes the audience through to the passage of the 19th Amendment in 1920 and then does a forward jump to 1970, when we encounter the older Alice Paul who gets her age-related comeuppance from a younger feminist sent by the National Organization for Women (N.O.W.) and who is played by a Black actor (Laila Erica Drew).

The Trouble with “SUFFS” White Feminism

If you have even a 101-level of understanding about the passage of the 19th Amendment, you know that there was an epic struggle, including Susan B. Anthony saying to Frederick Douglass, “If you will not give the whole loaf of justice to the entire people, it should be given to the most intelligent and capable portion of women first.” Of course, she meant white women. This is part of what prompted Black feminist scholar bell hooks to write, almost a century later, that the 19th Amendment was more a “victory for racist principles than a triumph of feminist principles.”

This struggle is largely excised from “SUFFS” in favor of the blandest, flavorless, and ultimately quite dangerous version of white feminism.

In Act I, there is a musical number, “G.A.B.” that’s meant to be a rousing anthem of feminist defiance in claiming the term “bitch,” as in “Great American Bitch.” This number is supposed to be part of the show’s theme of “trailblazing,” but it mostly evokes the meager set of ideas on offer from a gender-only view of feminism.

Gender-only feminism is when people do that thing of “men are….” this way and “women are…” some other way. You know, Mars/Venus kind of bullshit (great podcast debunking that here.)

This gender-only feminism is exactly what I found when I spent time at the “Ladies Only” forum at a notorious white supremacist portal for my research. The women there talked about how “silly and useless” men are, how women deserved equal pay for equal work, and they thought abortion should be allowed sometimes and it should be a woman’s decision. They sounded like they were at a National Organization for Women (N.O.W.) meeting. This led me to write:

“To the extent that liberal feminism articulates a limited vision of gender equality without challenging racial inequality, then white feminism is not inconsistent with white supremacy. Without an explicit challenge to racism, white feminism is easily grafted onto white supremacy and useful for arguing for equality for white women, and possibly for white gays and lesbians, within a white supremacist context.” (Cyber Racism, 2009).

The feminism in “SUFFS” is gender-only feminism like the “Vagina Monologues.” It seems designed to appeal to the set of feminists who found social media to be a place of “toxic feminist wars” and who think that “Karen” is a joke that’s gone too far.

Gender-only feminism uses distraction —- look at this, not that! — to get your attention focused on misogyny while it distracts you from the ways that misogyny and racism are intertwined. It smuggles in the racial project of comforting white women about their place in a white supremacist system by getting you to pay attention to the ways white women suffer under patriarchy (in this way, the title is a double entendre, the “SUFFS” suffered, the playwright wants you to know). It does this by first convincing the imagined audience that we are ONLY gendered subjects (women), and therefore oppressed even as it distracts us from the fact that we are ALSO racialized subjects (white), and therefore implicated in white supremacy.

The musical number “G.A.B.” can only be a rousing anthem for white women, and that is who is on stage to sing it. It is one of the many cringe moments in the show as it suggests the controversy over “SlutWalk” marches from around 2011. As I and lots of others have explained elsewhere, the version of feminism that seeks to reclaim pejorative terms like “bitch” or “slut” is neither appealing nor available to everyone. In a 2016 missive called “Open Letter from Black Women to the SlutWalk,” a collective of authors challenged this approach to feminism as exclusionary and harmful. We can’t just “bitch” our way out of misogyny and patriarchy. This is the trouble with white feminism: offering a supposed political anthem that only works for a privileged few.

Everyone else will have to “Wait My Turn,” another song in the show’s first act. This song is meant to illustrate the intergenerational tension between Catt’s contingent of white activists (whom her character refers to as “nice white ladies”) and Paul’s younger, more impatient white suffragists. When the character Ida B. Wells-Barnett sings it back to Paul early in the first act, it serves to suggest the racial tension in the movement but then immediately contains and dismisses that challenge as the Wells-Barnett character (inexplicably referred to as “Mrs. Wells” here) exits the stage after that song and the play returns to the primary action involving the white suffragists.

In Act II, the suffragists are incarcerated for their protests at the White House, go on a hunger strike and in a dramatic climax, reenact the (historically accurate) force feeding by their prison officials. Until this point in the play, the State — here represented by Woodrow Wilson — is the site of redress for feminist grievances of Alice Paul and company. It seems ironic that in a country in which some 28.8 million people struggle with disordered eating, and there is still a cultural edict that women, particularly white women should be thin, that forced feeding by the State is the only violence that is of concern here. Meanwhile, the actual historical figures Ida B. Wells-Barnett and Mary Church Terrell were trying to get the white suffragists, including Alice Paul, to care about the violence of lynching, but Paul dismissed their work through the NACW as not a feminist group but a “racial one.”

One wishes the play’s creator, Shaina Taub, had read more widely than just the one book (Jailed for Freedom) about feminism in the Progressive Era because it’s a fascinating historical period that has the potential to teach us a great deal about gender, race, and the politics around voting.

Unfortunately, “SUFFS” repeats the worst mistakes of white feminists of that earlier era and generates new ones for the current moment. What the creators of “SUFFS” have produced is actually quite harmful beyond simply a rather dull night at the theater.

It is doing political work that undermines the work for our collective liberation, and for that reason I’ll be dedicating this entire week on here to a series of posts about different aspects of the play, including its use of colorblind casting, Black women as “feminist killjoys,” why the play is emerging at this particular moment, who the producers are behind the show and why that matters for all of us and our collective liberation. Buckle up!

I believe it’s worrisome that you are the one who is erasing the Black character’s scenes from your narrative, especially since it means that people might read this and believe you and not give a chance to a musical that’s telling the story of important people like Ida B. Wells and Mary Church Terrell with an exceptional cast that carries the messages of these women.

First of all, it would be great to know the place of the theater you are reviewing. In two of your essays, you’ve called it the wrong name which speaks lengths about the little research you’ve done before writing your review. Just so you know, it’s not “the magical box”.

Now, let’s get to the story. I will begin by saying I haven’t seen the show because I’m not privileged like some white people who claim to have seen it four times and I live in Latin America, but YET, I’ve read a lot about it and listened to its cast album. So I won’t make things up, I will quote from what I know it’s on the show.

You said “The musical begins in 1913 with Alice Paul (Shaina Taub, playwright and lead actor) organizing the Woman Suffrage Procession.” Yes, but you’re forgetting something before that. The musical begins with a song called “Let Mother Vote” which has some very curious lines, like “Let Mother vote, we'll keep our country clean” which coming from a white lady from 1913, it’s pretty obvious what is included in “clean”, but I’m autistic, I don’t understand figurative language so well, so maybe I’m wrong, let’s go with another example: “We'll vote like father, vote like son and two good votes are better than one”, I don’t think you have to be an expert to know that she means “good votes” as in “the votes of white people like me” and how she’s trying to double their votes (and gain more power like that!) and she makes it even more specific when she says that she’ll vote like husband and son. If the fact that Carrie Chapman Catt is racist is still unclear, don’t worry, it will be proven again later in the show in another song.

Let’s take a look at what you said again: “The musical begins in 1913 with Alice Paul (Shaina Taub, playwright and lead actor) organizing the Woman Suffrage Procession. As with any creative project, these are intentional choices that the play’s creators make to tell one particular story and exclude other stories.” How is the creator excluding other stories if, on the very same song in which Alice is organizing the parade (‘Find A Way’), she is shown as a racist after she tells Ida B. Wells to wait her turn? If people do not realize that that request is ABSOLUTELY racist it is not the show’s problem, but theirs. It is even more obvious because when the white suffs decide that black women should march in back Ruza, an immigrant, asks if she should march in back too, but no one asks that of her. Why? Because she’s white.

Later, on your review, you talk about the song “Wait My Turn” and you say “This song is meant to illustrate the intergenerational tension between Catt’s contingent of white activists (whom her character refers to as “nice white ladies”) and Paul’s younger, more impatient white suffragists.” I’m sorry, but how do you draw that conclusion from the song? Were you really paying attention to what the black actor in front of you was saying? This song is a response to Alice Paul’s racist request, the character who sings it is Ida B. Wells and at the very beginning she tells Alice “Wait my turn, when will you white women ever learn? I had the same old talk with Carrie Chapman Catt 20 years ago” which proves that not only is Alice being racist, but that the suffragist movement and Carrie Chapman Cott have been racists for A LONG TIME. And these new suffragists are doing nothing different even when they act like they are so modern in their ideas. I could just quote the entire song because I think its message is very accurate and needs to be heard and it’s full of lines that are very explicit about how racists the white suffragists are.

After you talk about it you say, “it serves to suggest the racial tension in the movement but then immediately contains and dismisses that challenge as the Wells-Barnett character (inexplicably referred to as “Mrs. Wells” here) exits the stage after that song and the play returns to the primary action involving the white suffragists.” But when you actually listen to the show, the topic is not dismissed after that. Did you hear the song “Terrell’s Theme”? I don’t think so, so I will tell you something: when it starts you can hear Mary Church Terrell’s daughter telling her “They don’t even want us here”. Again, it’s explicit that the suffragists were leaving black women behind. You say in your review that the NACW’s motto was “lifting as we climb” and you’re right, it’s also part of the song as they say “And so, lifting as we climb, onward and upward we go.”

And even after that, when the march begins there’s a moment worth mentioning. The song “The March (We Demand Equality)” begins with Inez Milholland and the Suffs voicing their demands, but then, the one who sings the solo part is Ida. Didn’t you feel the power of that when you heard it? How it acquires a new perspective and a whole new meaning when the demands come from a black voice? Ida says “We demand to be seen, we demand to be heard, we demand our dignity will never be deferred” IN the same march for which she was told to wait her turn and march in back.

You’re also not mentioning another significant moment in Act I which is the song “The Convention Part I” which shows the different stands between the black suffs. Mary is in the convention, a “white women’s convention” as they say in the song, to give a speech because otherwise “they wouldn't even mention race”. Again, the show is stating how easy it was for white suffs to forget about important topics like race because it wasn’t on their agenda. Moreover, in the song, it’s explicitly told that the white suffs are using Mary just to cover their racism.

I think that by the end of act I there’s no doubt that Alice Paul was not a hero and that white suffragists were racist even when they tried to hide it.

But race is not an abandoned topic in Act II. There, we have “Wait My Turn (Reprise)” in which Ida talks about her work against lynchings and how tired she is of fighting for it when things stay the same. She says “How many more thrown in nameless graves?

How many more falsely charged with crime? How many more whipped and shot like slaves? How many more murdered in their prime? How many more pamphlets must I write?”.

And then, the 19th amendment is passed and the white suffs celebrate, but the musical doesn’t end there and celebrations are interrupted in the song called “I Was Here” in which the black suffragists let us know that the fight is not finished yet. In that scene, Mary tells Ida about the passing of the amendment and Ida says “They did it” while Mary corrects her and says “We did it”. In that correction, they are recognizing that their work was needed for the cause, even if the white suffs didn’t see it. And then we hear the melody for “how long must women wait for liberty” and Ida says “They'll still stop our women from voting, same as they do to our men.” So we, as an audience, learn how little the whole fight did for these women. The white suffs can resume their lives, but they have to continue fighting, even if they were there for all of it. White women may have gained more liberty, but not ALL women.

Suddenly, it’s the year 1970, and a black activist is STILL fighting and she reprises a song that Alice Paul sings at the beginning and says “I don't want to have to beg for crumbs from a country that doesn't care what I say” years after Alice said it, the country is still turning its back on black women. And she finishes saying “Yes, I want to know how it feels when we finally finish the fight”. Because, again, it’s clear that the fight won’t be over until all women are equal and the voices of black women are heard.

Just one more thing worth mentioning. At the start of your review you state that the score doesn’t have any hummable tune. Do you know which composer was always criticized for that? Stephen Sondheim.

If this were Hamilton, you would have no problem with it. When a Jewish woman writes about a story that she enjoys, it’s not progressive enough, but it seems no one has any problem with the overall lack of female characters in other stories. This one had a cast of all colors, religion, and ethnic backgrounds, and you say it’s too white. The woman who wrote it isn’t even white, she’s Jewish! The hypocrisy is astounding: