Today, October 16, is the anniversary of John Brown’s raid on an armory at Harper’s Ferry, West Virginia in 1859. The goal of the raid by Brown and a dozen or so other men was to provoke an end to slavery. In his own words, Brown said:

I came here from Kansas and this is a slave state; I want to free all the negroes in this state; I have possession now of the United States armory, and if the citizens interfere with me, I must only burn the town and have blood.

Brown was captured and executed for this adventure in collective liberation, but not before his defense attorneys tried to line up an insanity defense with affidavits they neighbors who described him as a “deeply religious” and “very conscientious” man who was, at the end of the day, “clearly insane.” This view of Brown was solidified in historical accounts, such as Bruce Catton’s popular Civil War trilogy, which dismissed Brown as “unbalanced to the verge of outright madness.” Similarly, Allan Nevins, writing in the fourth volume of his series on The Ordeal of the Union, thought Brown suffered from “reasoning insanity, which is a branch of paranoia…marked by systematized delusions.”

The muralist, John Steuart Curry, solidified the view of Brown as mad in his series of panels memorializing Kansas history for the state capitol in Topeka. Curry’s mural called, The Tragic Prelude, features Brown in the center, his arms open wide, with an open Bible in one hand and a rifle in the other. The mural, of course, is a reference to the Civil War, and the image suggests that it was Brown’s madness at wanting to end slavery that was what led to that conflict, rather than the horrors of chattel slavery.

This was the version of John Brown on offer in the curriculum of the Texas public schools that I grew up in. This notion of madness, of being so out of step with one’s own time as to be out of touch with reality, is one that has haunted me. Am I brave enough to be this kind of crazy? I heard someone, a Black man recently released from a psych ward, say that the rooms there are filled with people who simply see the world for what it is. I felt that with my whole heart.

Perhaps it is this thread of madness that has made me feel tethered to John Brown’s story and part of why I traveled to Harper’s Ferry a few years ago, just before I realized my life was coming apart (in 2018). On this trip, I took a bunch of notes, photographs, and even interviewed one of the curators of the exhibit there about what it is like to memorialize John Brown at Harper’s Ferry.

I spoke with a young white woman who had completed her master’s degree in public humanities, and so equipped, set out in 2012 to revisit the way Harper’s Ferry memorializes John Brown. This is “Nicole” (a pseudonym) who worked for the National Park Service (NPS) in 2018, here is some of our conversation, when I asked her about what it’s like to work there.

There is just so much tension around it. The NPS is obligated to protect its resources, this is a resource, now historical itself, what to do with it. The compromise was to put up this really vague wayside marker that doesn’t really delve into the controversy and let people figure it out. Harper’s Ferry can be hard enough with John Brown and such a polarizing figure. People come here with tremendous opposition, they see him as a terrorist and a traitor. On the first day I worked there, people came in wearing Confederate flag t-shirts. One guy said to me, “I hate John Brown, if this is a tour about John Brown, I don’t want to go on it.” Then, a lot of other people come here, and they have no idea who John Brown is.

The issue of John Brown’s madness is less salient in the plaques at Harper’s Ferry. Instead, there is an attempt to navigate the current political boundaries of red-and-blue in what gets included and what left out. There is very little, for example, about slavery and much more focus on the details about the Civil War that might appeal to those who are drawn to staging reenactments.

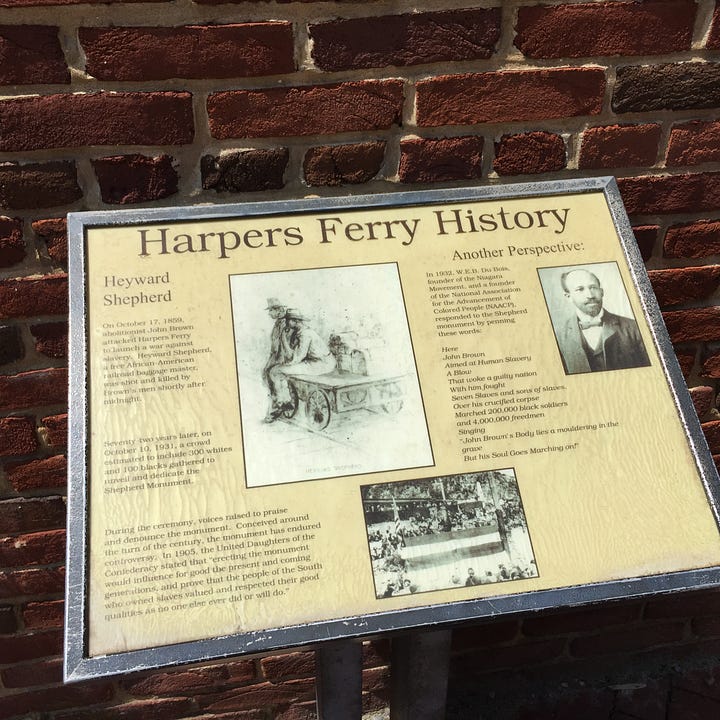

I was struck by how much of the material at Harper’s Ferry is about Haywood Shepherd, a free Black man who worked as a baggage handler for the railroad who was fatally shot by one of John Brown’s men in the raid. Why this story above all others? I asked Nicole about this, and she explained:

Yes, I was surprised by that, too. But then, as I got into the research about memorialization, there was this huge frenzy of memory-making about the Civil War, and the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) were especially involved in that. The UDC is still heavily involved as board members, and they make themselves very loud about any changes to interpretations, or to taking Confederate flags down. They are very vocal and have a lot of say at historic sites.

In 1931, the nice white ladies of the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) lead the installation of the memorial at Harper’s Ferry and used Hayward Shepherd’s death to revivify the “lost cause” narrative by asserting that those enslaved were “well clothed, well housed” and praising Shepherd as “exemplifying the character and faithfulness of thousands of Negroes [sic] who, under many temptations, throughout the subsequent years of war, so conducted themselves that no stain was left upon the records that is the peculiar heritage of the American people, and an everlasting tribute to the best of both races.” This celebration of propaganda was interrupted by Pearl Tatum, a Black woman who rose to express her outrage, and now there is a small plaque commemorating her protest.

Memorials are important for the way they narrativize the past. For the same reason, they are always contested. I think about Bryan Stevenson, civil rights attorney, author and founder of the Legacy Museum, and his wisdom often. He said, “the North won the Civil War, but the South won the narrative war.”

The challenge of the current moment is, I believe, to tell a more accurate narrative, one that can honestly reckon with the past so that we can face the present and create a better future. But that is formidable challenge in this political moment when consensus reality and the realm of facts are constantly under attack from misinformation, book bans, and the same political impulses that want to reanimate the “lost cause” narrative. Holding on to a vision of collective liberation in the face of all that will make you an outlier, and might even get you called crazy, but then you’ll be in good company.