Black Women Icons as Feminist Killjoys

In "SUFFS" Ida B. Wells-Barnett and Mary Church Terrell are the Killjoys

The play “SUFFS” opens in the year 1913, an artistic choice that anchors the audience in the life of suffragist Alice Paul (this is the third in this series, the first two posts are here and here).

Even the promo video featuring Hillary Rodham Clinton (producer) starts with the line, “In 1913 women in this country were not allowed to vote…” then a variety of cast members explain the suffragist movement as a political fight involving big hats and uncomfortable shoes. It ends with Clinton telling us that “the road to equality is long which is why we keep marching but in way more comfortable shoes.” Clinton is at her best here, relaxed, well-lit, and congenial.

We seem to be having a fight over our history, here in the U.S., stoked by figures on the far right who are determined to turn the clock back on hard-won political victories. Deplorable figures on the far right like Nick Fuentes say the quiet part out loud when they declare that women shouldn’t be allowed to vote and “should be treated in the U.S. the same way they are treated in Afghanistan under Taliban rule,” adding Islamophobia to his misogyny. Fuentes is not alone. It’s not just douchebags like Fuentes delivering this talking point. Pearl Davis is a (white) woman with over two million followers on YouTube who believes that “men are discriminated against” by society and especially by feminists; she also believes that women shouldn’t have the right to vote because that might interfere with our duty to take care of men, or something like that.

Some might say there has never been a better moment to focus on women’s right to vote than now, but a selective retelling of that history, one that begins in 1913, ends in 1920, and then skips ahead to 1970, does a different sort of work.

“The Red Record” to Equal Justice Initiative: Documenting Lynching, 1880-1940

Growing up in Texas and going to public schools there, I didn’t learn about lynching until I was in graduate school. It was then I read Hazel Carby’s brilliant piece on the violence of empire. In that, I discovered the work of Ida B. Wells-Barnett and her investigative work, “The Red Record.”

In the summer before the passage of the 19th Amendment, the U.S. experienced something known as “Red Summer.” In July, 1919 rumors began circulating among white residents of Washington, D.C., that a Black man had sexually assaulted a white woman. When the news spread that police had released a Black suspect from custody, white people began a violent rampage against the Black community in D.C., and that white-led mob violence spread to multiple cities across the nation.

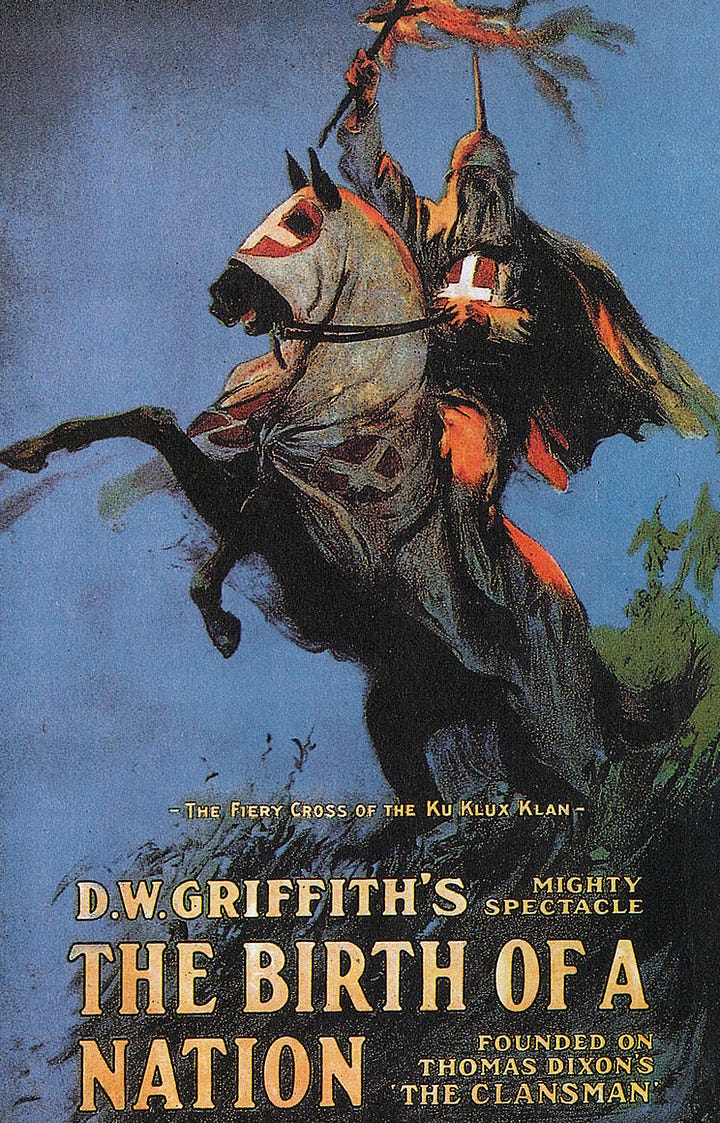

It was these extrajudicial murders of Black people that Ida B. Wells-Barnett documented in her series “The Red Record.” In her investigations, she found no evidence to support the claim that white women were being sexually assaulted by Black men. She referred to this assertion as a “thread-bare lie.” It’s this “thread-bare lie” that is the main story in Birth of a Nation, the 1915 film and piece of Ku Klux Klan propaganda that Wilson screened at the White House, another historical fact not mentioned in “SUFFS.”

According to the Equal Justice Initiative, “terror lynchings,” peaked in the period between 1880 and 1940. The practice ended the lives of African American men, women, and children. In 2018, civil rights attorney Bryan Stevenson, founded the Equal Justice Initiative and established the nation’s first ever lynching memorial dedicated to honoring those who were murdered in this way, and when it opened the New York Times declared the “country has never seen anything like it.”

It is a moving, and unsettling, experience to go there. Christina Sharpe has an exquisitely written account of visiting the memorial in her award-winning book, Ordinary Notes. The experience is intended to be transformative, if you allow yourself to be changed by it, but we who are raised-white are often not equipped to embrace change, locked as we are in our fear, dissociation, and fantasies about our own innocence.

For me, the trip to Montgomery and the lynching memorial confirmed what years of research had revealed: that it is impossible to separate out “gender” from “race” in the simplistic way that white feminism wants to do. The underlying logic, if you can call it that, of white feminism is that it wants to make claims for ALL women while it simultaneously roping off race, and thus Black women’s experience, as a separate issue. When race is addressed, it doesn’t adhere to white women in that same way it does to Black women. In “SUFFS,” the whiteness of the main characters is largely unremarked upon (save the one “nice white ladies” mention early in Act I), while the Black women characters are hypervisible avatars of race.

Black Women as Feminist Killjoys

There are two characters in “SUFFS” based on historical figures and played by Black women: Ida B. Wells-Barnett (Nikki M. James) and Mary Church Terrell (Anastaćia McCleskey). Three, actually, if you include Terrell’s daughter, Phyllis (Laila Drew), whose role became a barely-speaking part when the production moved to Broadway. The failure to explore the mother-daughter dynamic between the Terrells for the resonance with Shaye Moss and Ruby Freeman, election workers vilified by far right thugs, is another missed opportunity in this production.

For reasons that are never explained, the character Ida B. Wells-Barnett is referred to as “Mrs. Wells” instead of by her married name, an interesting choice given the racial etiquette of Jim Crow segregation. But audiences of this play will not learn about Jim Crow. Both Wells-Barnett’s and Terrell’s roles are significantly smaller from the previous version at The Public Theater in 2022, when both these characters had more robust parts. While Wells-Barnett is on stage as much as in the earlier version, she speaks less now. And, in the Broadway version, rather than give a speech to the audience as she did before, Terrell’s character is positioned on stage with her back to the audience, gesturing from a podium and quite literally without a voice as the white actors take up downstage center. Terrell’s character here is one-dimensional and meant to serve as a moderate foil to Wells-Barnett’s more radical views.

Early in Act I, the Ida B. Wells-Barnett character joins in singing “Wait My Turn,” originally sung as a challenge to the older activist, and here turned into a challenge to Alice Paul and the other suffragists. As she sings, the suffragists stand around looking uncomfortable and the early momentum of the show slows way down. The song gives voice to an obvious Black feminist critique of the entire show but then contains and dismisses it as it moves on to the real action among the suffragists led by Paul.

When Wells-Barnett and Terrell come together on stage after the passage of the 19th Amendment in Act II, the music slows once again and they sing a somber number that kills the jubilant mood of the Suffs’ victory. It is a dramaturgical choice that situates these two characters as “feminist killjoys,” Sara Ahmed’s term for a person of any gender who makes others uncomfortable by pointing out the inequality of the status quo. (I, too, am a feminist killjoy for my refusal of the show’s message and my critique.)

While the creators of the show want to champion women’s activism with the song “Keep Fighting” (as in the promo video), the play contains a deeply conflicted message about activism. In Act II, best friends Lucy Burns (Ally Bonino) and Alice Paul (Shaina Taub) return to a theme throughout the play for the white suffragists, which is a tension between having a family and being an activist.

There is no such conflict even hinted at for the Black women characters. In part, this is because they are so one-dimensional (e.g., the non-speaking Phyllis Terrell and Mary Church Terrell pantomiming a speech). The white women suffragists lament their activism as a kind of burden when they sing, “is it worth it?” In the pivotal scene between Burns (Bonino) and Paul (Taub), Burns rips off her suffragist sash and throws it to the ground defiantly, presumably stomping off to live some heteronormative dream with a husband and children and a picket fence. At this point in the show, my theater-companion leaned over and whispered, “It’s giving: if Hillary were president, we’d all be at brunch vibes,” referencing one of the signs at the Women’s March in 2017.

The real action in the play stops with the passage of the 19th Amendment in 1920, then catapults the audience to 1970 for what amounts to an epilogue. The selection of these dates in history leave out an important part of the story of white women’s suffrage, and that’s what happened in the decade that followed passage of the 19th Amendment.

First the 19th Amendment. Then the Women of the KKK.

The fantasy of “SUFFS” is that the 19th Amendment passed, things got slowly better for women until Hillary ran for president. But it’s a fantasy that only works if you do that trick where you fuzz your eyes so that you can’t see something clearly (tricks from a dissociative childhood). What happened in the decade immediately after the passage of the 19th Amendment was a huge growth in the Ku Klux Klan, the notorious white supremacist group.

In her classic book, Women of the Klan: Racism and Gender in the 1920s, sociologist Kathleen Blee shows how the very expansion of white women’s access to the franchise laid the foundation for a hate group that was “by women, for women and of women.” They started the Women of the Ku Klux Klan (WKKK), and many in the WKKK had previously been involved in local campaigns for suffrage. As white women’s political opportunities expanded, many felt their role in the Klan should too. Launched in June 1923, “the WKKK embraced ideas of racial and religious privilege” Blee writes. In 1925, they marched down Pennsylvania Avenue in an aggressive endorsement of white supremacy. Between 1920 and 1925, estimates are that the Klan’s membership grew to between two to five million people, including both men and women. In interviews with Indiana Klanswomen nearing the end of their lives, Blee says she was surprised to learn that many did not feel remorseful for their role in the WKKK. I am somewhat less surprised because they saw their WKKK activism as perfectly aligned with their values in other political fights.

Progressive era politics around prohibition, and the white-woman-led Women’s Christian Temperance Union, a precursor to Nancy Reagan’s racist “just say no” campaign, also fueled the politics of the WKKK. Part of the way the WTCU did this was by positioning white women as “municipal housekeepers,” best suited for cleaning up the public sphere.

The reality is that white women who were involved in the suffrage movement and the often overlapping temperance movement did gain valuable political skills. After the passage of the 19th Amendment, many of those women put those skills to use in the service of overt white supremacy.

White Feminism is White Supremacy

In “SUFFS” white feminists take center stage and Black feminist icons Ida B. Wells-Barnett and Mary Church Terrell are diminished and pushed into minor characters. These artistic choices serve the show’s creator (Taub) and her benefactor (Clinton) but it doesn’t serve the rest of us who are interested in collective liberation for everyone.

Make no mistake: white feminism is white supremacy.

Make no mistake: white feminism is white supremacy. The trouble is that we who are white-raised have so deeply metabolized a series of “thread-bare lies” — about Black men as “super predators,” about white women’s innocence and victimhood — that we are unable to see and understand white supremacy when it is dressed up with suffrage sashes instead of pointed hats.

There is so much dangerous to our collective liberation in this show that I’ll spend two more posts contemplating why “SUFFS” is on Broadway in 2024 and why the show has attracted the producers it has, and why it must close before it does more damage.